“I hope you row well. Because you are sailing in the wrong direction!”

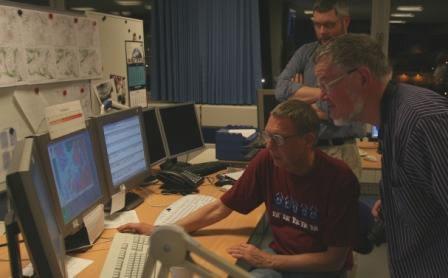

This was the brief and clear message to the crew of the Sea Stallion, when 25 shipmates Thursday night visited DMI - Denmark’s Meteorological Institute.

The words came from meteorologist Morten Sørensen. He has been with the DMI for 3 years but knows life at sea first hand. For many years he sailed as 1st and 2nd mate in the shipping companies Maersk and Scandlines.

Bluntly, the problem for the Sea Stallion is the direction.

When the world’s biggest reconstruction of a Viking ship sails from Roskilde this summer, it goes North of Scotland and on to Dublin; directly against the dominant winds. That is to say the British Islands and Denmark are right in the middle of the ‘low-pressure highway’, which starts in the northern Atlantic Ocean, where the low-pressures emerge. When the low-pressures have established themselves – almost like cars in rush hour traffic – they drive eastwards, unswervingly towards Great Britain and Denmark.

Cross your fingers for a southern low-pressure

A voyage of 1,700 kilometres against the wind sounds like a rough affair, but it does not have to be all that bad according to Morten Sørensen:

“When you are heading over the North Sea and into the Atlantic Ocean, you should definitely cross your fingers and hope for a line of low-pressures passing South of Denmark. If the low-pressures move down through northern Germany, it results in wind from East to West at the northernmost border of the low-pressure”.

In the Northern hemisphere it is like this: low-pressures are spinning counterclockwise. The case is opposite with high-pressures, which spin clockwise in the northern hemisphere. Furthermore the whole thing is the other way around in the southern hemisphere… though there are no current plans to send the Sea Stallion across the Equator any time soon.

A high-pressure above Scandinavia could yield winds from the East, releasing the crew of the Sea Stallion from rowing days on end and blisters the size of apples.

The rough seas of Orkney

With a worried frown meteorologist Morten Sørensen asked, whether the Sea Stallion was to go through the infamous Pentland Firth – the narrow straight between Scotland and the Orkney Islands, supposedly one of the most difficult passages in the world to navigate and without comparison the roughest in Europe.

As written elsewhere on this home page, skipper and his masters after travelling North Scotland decided to find a short cut through the archipelago that divides the North Sea from the Atlantic Ocean.

“I am pleased to hear that; because Pentland Firth is rough stuff with very strong currents and challenging surf. The waters are so rough that even the big container ships from Maersk with 100,000 horse powers in the engine room go around, if a storm is brooding.”

And the forces of the seas are not to be messed with. At DMI the meteorologists keep an eye on the weather at sea. Based on the observations they produce suggestions for route plans for the shipping companies. It has happened though, from time to time that a stubborn captain has disregarded the DMI’s suggestions. When the storm rages even 42 millimetres sheets of hard steel are torn apart and a 20 ton anchor ripped off of the ship.

Reliable forecasts from the East

Morten Sørensen also had the surprising anecdote to share with his audience that weather reports are usually more reliable, when the weather comes from the East, than is the case, when it comes form the west. As simple as it is this is due to the fact that there are many weather stations on land while in the Atlantic Ocean the ships and weather buoys observing the weather at sea can be hundreds of kilometres apart. The more observations – the better the weather forecast.

In accordance to this, one of the Sea Stallion’s three masters, Poul Nygaard, wanted to know, how quickly a low-pressure could emerge, if not forecast.

If we are at Stavanger in Norway in July and decide to make for Orkney, because the weather is good without the slightest sign of a low-pressure – how much time would we have?

”Low-pressures can come up very fast; especially if it is one of the polar low-pressures with very cold air blowing down from the North. But you sail in July, so I find it hard to believe that you should be hit by an un-forecast polar low-pressure. It is your fortune that the prognoses in summer are good. But you may be unlucky if the polar front reaches Scotland and southern Norway, usually it is quite a bit further North. Along the polar front sudden and un-forecast low-pressure do appear,” Morten Sørensen explains.

DMI by the numbers

DMI has 400 employees; about 70 of these are meteorologists. DMI constructs its forecasts on observations from seven different sources:

Ice recognisance near Greenland, where ice bergs can be the size of Zealand. Data on the movement of the ice is of great importance to seafaring. Maps of the ice are issued once a week.

Weather data from ships and buoys on the open sea.

100-150 weather stations spread across Denmark.

Weather balloons sent skyward twice a day (at noon and midnight). The balloons send data every second metre all the way up to 30-35 kilometres, where the balloon collapses and drops to the ground.

Two types of weather satellites. One circumnavigates the globe from pole to pole at an altitude of 800 metres. A complete circuit takes an hour and a half. The other type is the geostationary satellite, at 36,000 kilometres it stays in orbit over the same spot on earth.

Weather radar monitoring rainfall for example.

Airplanes which automatically submit data to the DMI.

All this data is gathered in a supercomputer and is the base of the meteorologists calculations and forecasts.